ARTISTs IN RESIDENCE | APRIL -MAY 2016

|

JENNIFER LANE is a California-based playwright, novelist and teaching artist originally hailing from Detroit, Michigan. She is the Playwright in Residence at the Scripps Ranch Theatre, and the co-moderator of their New Works Studio. Her work has been presented at or developed by the terraNOVA Collective, the Gulfshore Playhouse, Sightline Theatre Company, Artistic New Directions, IRT, The Bridge Theatre Company, the New Ohio Theatre, 3LD Art & Technology Center, the Gene Frankel Theatre, Theatre 54, Manhattan Shakespeare Theatre, The Washington Rogues, Gorilla Tango Theatre, Columbia Stages, LiveGirls! Theatre, Mission to (dit)Mars, NYCPlaywrights, The Actors Theatre of Charlotte, The Culture Project, the Inkwell Theatre, and Scripps Ranch Theatre.

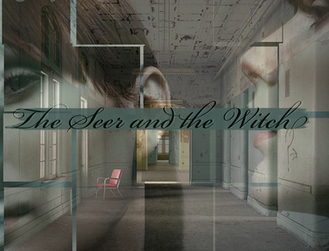

Her plays include September & Her Sisters (Scripps Ranch Theatre's Out On A Limb Festival, 2015); The Seer & The Witch (developed in the Groundbreakers Playwriting Group at terraNOVA, part of the nuVoices for a nuGeneration Festival, a Semi-Finalist of the O’Neill Playwriting Conference, nominated for the Susan Smith Blackburn Prize); Harlowe (developed under the mentorship of Sarah Ruhl, winner of the Alec Baldwin Fellowship at Singers Forum, and workshopped at the Gulfshore Playhouse); Psychomachia (recipient of the Gatsby Grant and produced at Theatre 54); The Would-Be Room (performed in New York City, Chicago and Washington D.C.); Convergence (premiered as part of the soloNOVA Festival); The Burning Brand (workshopped at Playground @ The Old Globe); and Does Anyone Know Sarah Paisner? (produced at the Gene Frankel Theatre). Her short pieces A Fever in the Feast and Uriel’s Garden were both workshopped with Anne Bogart. Fever…, as well as another short play, PIN, was performed at Ensemble Studio Theatre in early 2011. Tummy Bubbles was the NYCPlaywrights play of the month for February 2013, one of the Samuel French Off Off Broadway Short Play Festival’s top 30 Plays, and part of the Culture Project’s Women Center Stage Festival. Her short play i am the girl with the spun gold hair was produced at LiveGirls! Theatre in Seattle, WA. Jenny is a graduate of Columbia University — where she was taught by such remarkable artists as Chuck Mee, Anne Bogart, Lucy Thurber, Sheila Callaghan and Kelly Stuart — and Sarah Lawrence College. She is an alum of the terraNOVA Collective Groundbreakers Playwriting Group and the Mission to (dit)Mars Playwriting Group. Currently, Jenny is a teaching artist with the Playwrights Project, San Diego Writers, Ink, and UCSD Extension. Her dramatic writing is represented by Amy Wagner of Abrams Artists Agency in New York City. |

Renzo Marasca - painter website

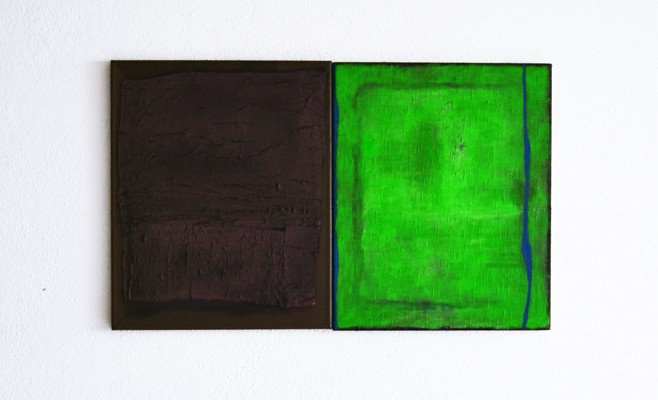

Artist in residence April-May in preparazione della mostra a cura di Carolina Lio che inaugurerà il 14 maggio. Is it really necessary to identify the contemporary painting as conceptual or narrative? In other words, do we really consider as a good painting only the one that put itself in the service of a didactic, social or intellectual thought? Does a painting that does not narrate or philosophize, that does not lend itself to become just a noble version of the illustration or a mere appendage of the installation, no longer have a reason to be? To go along with this idea means to support that part of the critics who says that painting is dead. Still, Renzo Marasca works on this middle ground, a research left unfinished by those who could - and should - be the heirs of Bacon and which have instead neglected all his discoveries on the idea of space and figure in painting, focusing only on the turbid and restless vision of man that emerges from his masterpieces. So, the new generation of painters has too quickly forgotten that at the base of his geniality and of other pictorial experiences of the twentieth century, there was not only a modern human research – moreover already explored by other disciplines – but, above all, a research on the material and on the space of the painting, a research that was supposed to upset the basic idea of this technique, freeing it from the representative function that had forced other artists through the centuries, and giving it the opportunity to develop a new dignity and strength as a solid and complete means. Research in painting, seen in this light, is an inexhaustible field because it overtakes the argument and the thought. It becomes a compositional challenge in which man brings himself beyond what of himself he could describe and analyze. As Gerhard Richter says: "I do not demand an explanation from myself as to why this is so" and talks about his work in terms of experience, of management of the material, of color control. Renzo Marasca is an artist who every day, for his entire day, works on the growth of this type of control and of the management of the pictorial matter. Or he works on himself, on a growth more personal than intellectual, a training that he feels as a need in order to deal every day with that confined and yet empty space that must be continuously created and organized, searching for the form in itself, for the painting as a body and not just as a sense. For the matter beyond rationalization.

For this reason, to talk about "landscape" and "nature" in his work is inappropriate if one does not make certain specifications. Sure enough, his purpose is not to repeat any pre-existing figure, although in his studio they can be found photocopies and photographs of various subjects, including elements of nature. But these do not serve as subjects and models, but as a distant inspiration to build those spaces and forms that, to the demand of an observer in need of something to recognize, respond seeming landscapes. However, the correspondence is loose as much as that of some optical tricks such as the “Kanizsa's triangle” or the “illusion of Ehrentein” that leverage on the needs of our brain to fill in the gaps and create missing links in order to reconstruct in our mind something predictable and known. Seeing landscapes in his works - something that I have noticed to be common - is therefore more a preconceived mechanism of thinking that painting should simulate something. A thought born out from our limitation of not being able to conceive it as a structure on its own, independent, able to reorganize itself in a sense that not just borrows meanings from the outside world. Instead, Renzo Marasca succeeds, by a process of action that, if it had not already been beaten by brilliant minds such as Gerhard Richter and Cy Twombly, it would be even premature respect to the image of art we have managed to achieve so far. His "landscape" is, indeed, something that is not structured in a solid and concrete form, it does not appear as a geographical object but as an ideological phenomenon in which the matter, object of nature, takes its own stand. Obviously, it is not a political ideology, nor philosophical, nor literary. Many times, talking with Renzo about critique and art, he tends to strongly clarify he is not an intellectual by profession and that he leaves to the others this role, effectively constraining. His knowledge which, in any case, is unquestionable, remains out of the frame, circumscribes it and in a certain sense presses against its perimeter because it forms humanely the person who becomes painter and acts on the picture. But his culture remains outside, does not really belong to the work. The painting is free, indeed, it devoids of any intellectual vices and responds only to its own internal architecture in which the stands taken are not concepts but intuitions about space and about the way to place the matter in relation to nothing else than itself, letting it live its own instinctive intelligence. Much more difficult is to explain this work how less it is didactic. It is difficult, indeed, to describe that form of wild intelligence that belongs to the artist who works on the body of the painting, abandoning the two roads easy to make and to describe, those two already mentioned at the beginning of this text: the descriptive face and the conceptual one. Once removed these two garments, wearing and outerwearing, an artist who decides not to use them, tackles a full contact fight between himself and a surface on which he must create a new level of perception. Abandoning the commercial position of those who must allow the audience to see in the picture what it likes most, and abandoning also the snob conceptual vein of who must demonstrate he had a very thoughtful work so much that the work could then even not be made at all, it remains a bare effort to understand what the painting actually is. Which sense actually has to take an empty space and try to create out new forms of subtle intellect, rough intelligence, something that is closer to the spontaneous bunching of the forms of life to create an organism, than to the posed, studied also in its transgressions and calculated world that is contemporary art. For this reason, Renzo Marasca lives painting as a conflict. A conflict between how much of himself must be inserted and how much should instead be hidden to let the material make its own considerations. How much can he afford to reason consciously before that goes to contaminate the work leaving a halo of virtuosism. How much instinct can actually be use before the work loses its intrinsic freedom and before it becomes an outburst of the artist. How much can he take from the world and from art without losing the sense of a creation. How much can leap before his creative ambition loses control and breaks the balance of the work. Sure enough, it is like an arm wrestling in stalemate, where two powers - the artist's and the one that belongs to the painting as part conceived and respected as sentient - push in equal and opposite directions. But not with the calibrated elegance of the physics' forces, as with the animality of challenge between bodies. The result is always a form of dissatisfaction, inevitable in this stalemate, in which the artist feels himself unable to reach that spark of divine genius, the transmutation from a human thought to a purely pictorial one. Yet not succumbing and not jumping to one easier side of understanding art, yet continuing a dialogue on par with the materials, yet governing the construction of the canvas by balancing his own conscience and the one, impenetrable, of the painting itself, distinguishes who is an artist for “manner” and who is it for “essence”. Renzo Marasca, certainly, in my experience, is one of the few artists to be seriously what this role requires: a form of intelligence that abandons any sophisticated softness in order to clash with the body of the art, addressing the painting as an unforeseeable creative means, physical and violent in its rude materiality that can be handled without ever being domesticated in ways that no other language couldn't never explain. (Critical note by Carolina Lio) |